2023 CYBER SECURITY TRENDS

WIPER DISRUPTION

PLAYER ON GEOPOLITICAL STAGE

LEGITIMATE TOOLS

SHIFTING FOCUS FROM

ENCRYPTION TO DATA EXTORTION

THE RISK OF TRUSTING THE

FAMILIAR

THREAT

The ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war has had a profound effect on cyberspace and caused a significant increase in cyber-attacks in 2022. Hacktivism has been transformed, and the use of destructive malware by state-sponsored groups and independent entities has become more prevalent globally.

The role of cyberwarfare has been well documented in this first full-blown hybrid conflict, where battles are fought online as well as on physical ground. The Russians revealed new cyber tools and achieved tactical objectives that affected military and civil communications, including blocking public media transmissions. While cyber activity cannot win the war on its own, it does play a significant part in tactical operations and has an indisputable psychological and economic effect.

For cyber-operations to be effective, is not just a matter of employing malware. Much like conventional warfare, cyberwarfare also requires meticulous and thorough preparations. Reconnaissance, intelligence gathering and assessment, target-bank compilation and prioritization, dedicated-payload development and network infiltration are all prerequisites for a successful campaign.

As was the case on the physical battleground, the Russians apparently did not prepare for a long cyber campaign. Their cyber operations, which in the early stages included carefully planned precise attacks, have all but ceased. Multiple new tools and wipers, that were characteristic of the initial stages, have been replaced with a different operational mode. Current offensive cyberattacks are mostly rapid exploitations of opportunities as they arise and use already known attack tools. These are not intended to assist tactical combat efforts but rather create a psychological effect by damaging the Ukrainian civil infrastructure.

The recruitment of cyber professionals, criminals, and other civilians to the military cyber effort - on both sides of the conflict - has further blurred the distinction between nation-state actors, cyber criminals, and hacktivists. The Ukrainian government has established an army of hacktivists whose management is very different from anything we have seen before. Previously characterized by loose cooperation between individuals in an ad hoc fashion, new-hacktivist organizations conduct recruitment, training, intelligence-gathering and allocation of targets and battlefield status compilation in a military manner. Attacks on Russian entities, which were once considered off-limits by many cybercrime entities, have now increased and Russia is struggling under an unprecedented hacking wave that combines state-sponsored activity, political cyber warriors and criminal action. On the other side, multiple Russian-affiliated hacktivist groups were established that target not only Ukraine but also Europe, North America and Japan. For more details, see our section on Hacktivism.

The extensive use of destructive malware has already resulted in an increase in similar activities in other regions and by other geopolitical groups. Can cyberattacks be considered a hostile act? What type of proof, and how extensive must the damage be to be considered a casus belli? Are modifications to existing treaties required? We address these questions in another chapter of the report entitled "Wipers".

Eight years of continuous cyber hostility between Russia and Ukraine have served as a training period for both sides. Ukraine’s cyber defense organizations are praised as “the most effective defensive cyber activity in history”. Knowing adversaries tools and modus operandi has an increased importance in cyber warfare. The impact of a first-time deployment of a particular wiper may be devastating, but the impact of the second one is often much smaller. For example, the effect of the Industroyer2 attack on the energy sector in Ukraine in March 2022 was limited in comparison to Industroyer’s first deployment in 2016.

The full scope of changes brought on by this conflict is yet to be seen, but we have already learned some valuable lessons.

Wipers and other types of destructive malware are carefully designed to cause irreversible damage, and if tightly woven into cyberwarfare, the effect can be catastrophic. This is probably why we have only seen limited use of wipers over the years, and they were usually associated with nation states. Until recently, countries primarily used cyberattacks for the purpose of espionage and intelligence gathering, and only rarely resorted to destructive cyber tools. In 2022 we have seen a change in the appearance of multiple new wiper families that are used to destroy thousands of machines.

Wipers are destructive malware, designed to inflict damage with limited potential for financial gain for attackers. Early use of wipers to showcase attackers’ capabilities was thus limited and short-lived. But in all the cases, the main purpose of the wipers is to interrupt operations or to irreversibly destruct data. While the process of data destruction has several technological implementations.

Stuxnet, arguably the most famous destructive malware, was used in 2010 to sabotage the centrifuges in the Iranian nuclear project. At the time, Stuxnet was unique in many respects but mostly because its immediate impact was the physical destruction of mechanical hardware. In 2012, Shamoon, was deployed to disrupt oil companies in the Middle East, targeting Saudi and Qatari facilities. In 2013, DarkSeoul, attributed to North Korea, was used to destroy more than 30,000 computers related to the banking and broadcasting sectors in South Korea. This attack took place during a period of heightened tensions between the two countries following nuclear testing by the North.

In the ensuing years we witnessed the Black Energy attack in 2015 on the Ukrainian energy infrastructure (KillDisk) and another attack on Saudi targets by dubbed Shamoon2 in 2016. NotPetya was distributed against Ukrainian targets in 2017 in a supply chain attack which caused significant collateral damage globally. In 2018 Olympic Destroyer, purportedly produced by North Korea, was used by the Russian-affiliated Sandworm to disrupt the opening ceremonies of the Winter Olympic Games. In 2019 Dustman and ZeroCleare were used in Iranian attacks on targets in the Middle East related to oil production. On average, there was one attack by a wiper family per year.

During 2022, there has been a noticeable shift in the tactics of destructive malware deployment. Cyberespionage continued, as it was previously, but this activity has been supplemented by destructive cyber operations, instigated by nations whose goal appears to be to inflict as much damage as possible. The start of the Russian-Ukrainian war in February saw a massive uptick in disruptive cyberattacks carried out by Russia against Ukraine. Russia has a long history of cyber assaults against its neighbor. In January 2022, WhisperGate was used to attack government and financial organizations in Ukraine, overwriting systems’ MBR (Master Boot Record) to prevent system reboot and file recovery. Attackers left a ransom note but did not offer a recovery mechanism, leading to speculation that the demand for payment was only intended to mislead victims. The files were further corrupted using a second stage payload that was hosted on a Discord channel.

On the eve of the ground invasion in February, three additional wipers were deployed: Hermetic wiper, HermeticWizard and HermeticRansom. The tools were named after their certificate which was issued to ‘Hermetica Digital Ltd’. Additional wipers were reported later that month. Another attack was directed at the Ukrainian power grid in April, using a new version of Industroyer, the malware that was used in a similar attack in 2016.

In total, there were at least nine different wipers deployed in Ukraine in less than a year. Many of them were most likely separately developed by different Russian intelligence services and employed different wiping and evasion mechanisms.

One of the attacks, enacted hours before the ground invasion of Ukraine, was intended to interfere with Viasat, satellite communications company that provided services to Ukraine. The attack used a wiper called AcidRain that was designed to wipe modems and routers and cut off internet access for tens of thousands of systems. There was also significant collateral damage, including thousands of wind turbines in Germany.

The attacks were clearly the result of detailed planning. Some of the tools were designed specifically to fit their intended targets, with attackers breaching security measures and gaining access months earlier and then using GPOs (Group Policy Objects) to deploy their wipers at the time of the actual attack.

Cyber destructive activity was not restricted to Russia-Ukraine. In the Middle East, Iran has suffered a series of destructive attacks since the middle of 2021. In July 2021, a hacktivist group identifying itself as Predatory Sparrow attacked Iran’s railway system, causing delays and general panic. An investigation by Check Point Research (CP<R>) revealed that older versions of the wipers were used in attacks against multiple targets in Syria.

In January 2022, the Iranian state broadcasting service IRIB was attacked by destructive malware. The attack, investigated by CP<R>, caused damage to computers at dozens of TV and radio stations throughout Iran. Images of the leaders of the Iranian opposition, the anti-regime organization Mojahedin-e-Khalq (MEK), were aired on TV screens across the country, calling for “Death to Ayatolla Khamenei!” MEK, which conducts much of its activity from exile in Albania, denied responsibility. In June, the Chaplin wiper, a revised version of Meteor, previously used by Predatory Sparrow, hit steel plants in Iran. Other wiper attacks were reported in Iran that employed the Dilemma and Forsaken families but attracted less attention due to the general unrest in the country.

On July 18, just a few days before MEK’s conference titled “the World Summit of Free Iran”, the Albanian government stated it had to “temporarily close access to online public services and other government websites” due to disruptive cyber activity. The Homeland Justice hacktivist group that was behind the incident (later attributed to Iran) used various images and articles suggesting it was carried out in retaliation for attacks on the Islamic Republic. Researchers found that the wiper used in this instance, ZeroClear, is related to destructive attacks previously directed at energy-sector targets in the Middle East.

The MEK summit was cancelled, but this did not prevent a second cyberattack from hitting Albanian government systems in September. While this was an unprecedented attack on a NATO member state, the defense alliance did not consider it to be an ”armed attack” as defined by Article 5 of the NATO treaty. However the organization has in the past reaffirmed that cyberspace is part of NATO’S core task of collective defense. Iran has consistently invested in extending its foothold on western countries’ IT infrastructure. This bold act of deploying destructive malware against a NATO member without retaliation could have serious ramifications.

The destructive cyber activity continued throughout 2022. Somnia, a new wiper-turned-ransomware was deployed by the FRwL (From Russia with Love) hacktivist group against Ukrainian targets. The attacks resemble techniques practiced by ransomware groups, but no ransom demand was submitted, and the intent was clearly only to inflict maximum disruption on the victim. Similar attacks that deploy the CryWiper malware have recently been targeting municipalities and courts in Russia, leaving ransom notes and Bitcoin wallet addresses. However, in reality the damage is irreversible.

Azov is a new widespread wiper that falsely links itself to various security researchers and blames multiple nations and political entities for the current state of warfare. Azov has not been officially linked to any of the fighting sides and has been causing damage indiscriminately since November 2022, as detailed in a recent investigation by CP<R>.

More wipers have been used this year than were probably recorded in the past 30 years, and they have evolved both in the way they are deployed and in their impact. Some actors in this area are willing to take actions that could justify a war, modelling the definition of endured cyber hostility. It has become increasingly difficult to tell the difference between nation-state APT activity and hacktivist groups. Many countries are involved to a degree in the activities of non-governmental entities, ranging from providing inspiration, tools and target allocation, to direct management and financing of attacks disguised as private initiatives. This ambiguity further extends the degree to which threat actors can operate without the likelihood of retaliation. This will lead to more widespread destructive cyber operations and in turn ever higher levels of collateral damage.

Hacktivism, the act of carrying out politically or socially motivated cyberattacks, was traditionally associated with loosely managed entities such as Anonymous. These previously decentralized and unstructured groups were made up of individuals cooperating ad hoc for a variety of agendas. Over the last year, following developments in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, the hacktivist ecosystem has matured. Hacktivist groups have tightened up their level of organization and control, and now conduct military-like operations including recruitment and training, sharing tools, intelligence and allocation of targets. Most of the new hacktivist groups have a clear and consistent political ideology that is affiliated with governmental narratives. Others are less politically driven but have nonetheless made their operations more professional and organized.

The rise of politically motivated Middle Eastern groups in the past couple of years, such as the Iranian-associated “Hackers of Savior” or anti-Iranian regime “Predatory Sparrow”, marked the beginning of the change, as groups began focusing on a single agenda. Early this year, following Russian attacks on Ukrainian IT infrastructure at the beginning of the war, Ukrainian government set up an unprecedented arrangement called the “IT Army of Ukraine”. Through a dedicated Telegram channel, its operators manage more than 350,000 international volunteers in their campaign against Russian targets. On the other side of the battlefield, Killnet, Russia-affiliated group, was established with a military-like organizational structure and a clear top-down hierarchy. Killnet consists of multiple specialized squads that perform attacks and answer to the main commanders. These groups are led by a hacker called KillMilk.

Unlike Anonymous, who have an open-door policy, regardless of skill or specific agenda, the new era hacktivists screen out applicants who fail to meet specific requirements. This reduces the risk of exposing the inner workings of their operation. XakNet, a pro-Russian group, declared that they will not recruit hackers, pentesters, or OSINT specialists without proven experience and skills. Other groups, like the pro-Russian NoName057(16), offer training through e-learning platforms, tutorials, courses or mentoring.

Organized operations invest in and develop their members’ technical proficiency and tools. Although most of the activity is focused on defacement and DDoS attacks using botnets, in some cases, groups use more sophisticated destructive tools. TeamOneFist, a Ukraine affiliated group, has been linked to destructive activities against SCADA systems in Russia. The Belarusian Cyber Partisans group, in an attempt to prevent the movement of Russian troops to Ukraine, encrypted internal databases of the Belarusian Railways to disrupt its operation just before the invasion started. The pro-Russian group 'From Russia with Love' (FRwL) was observed using a data wiper called 'Somnia' to encrypt the data of Ukrainian organizations and disrupt their operations.

The battle is not only about inflicting damage. All active groups are aware of the importance of media coverage. They use their communication channels to collect reports of successful attacks and publish them to maximize the effect. For example, Killnet has more than 89,000 subscribers on their Telegram channel, where they publish attacks, recruit team members and share attack tools. There is also extensive coverage of the group’s activity in major Russian media outlets to promote their achievements in cyber space and validate the impact of their successful attacks.

Well organized and coordinated groups also use their resources to cooperate with other entities. Killnet’s success has put them in a position where other groups want to collaborate with them or officially join forces. On October 24, Zarya (Killnet’s squad) allegedly conducted a joint operation with two Russian-speaking groups, Xaknet and Beregini, to breach and leak data from the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU). In addition, Killnet recently announced the launch of a Killnet collective which has become an umbrella organization for 14 pro-Russian hacktivist groups.

The transformation in the hacktivism arena is not limited to specific national conflicts or geographical zones. Now major corporations and governments in Europe and the US are targeted by this new type of hacktivism. For example, in November 2022 the European Parliament was targeted with a DDoS attack launched by Killnet. In recent months, the US, Germany, Estonia and Lithuania, Italy, Norway, Finland, Poland and Japan suffered severe attacks from state-mobilized groups, with significant impact in some cases. New hacktivist groups are being mobilized based on political narratives and are achieving strategic and broad-based goals with higher success levels, and a much wider public impact than ever before.

Several groups in the Middle East, the most prominent being Predatory Sparrow, have been observed attacking high profile targets associated with the Iranian regime. The latest large-scale hacktivist attack was inflicted on Albania by ”HomelandJustice”, a hacktivists group affiliated with Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security. The group served Iranian interests by attacking the Albanian government who sheltered the “Mujahedin-e-Khalq” (MEK), an Iranian dissident group. Between October 2021 and January 2022 the group used a unique email exfiltration tool to collect emails. Then on July 15, they temporarily shut down multiple Albanian government digital services and websites using ransomware file encryption and disk wiping malware. These operations resulted in Albania’s termination of diplomatic ties with Iran on September 6.

The increased level of organization and specialization among hacktivist groups is not limited to political agendas. The Guacamaya hacktivist group targets entities in Latin America for their role in the region’s environmental degradation and repression of native populations. Since March 2022, the group has focused on infiltrating mining and oil companies, the police and several Latin American regulatory agencies. On September 19, Guacamaya leaked 10 terabytes of documents belonging to several entities in Mexico, Guatemala, Chile, Peru, Colombia and El Salvador. They also accused the United States and Western corporations of over-exploiting the region's natural resources.

Hacktivist operations, which until recently were marked by a spirit of anarchy and loose cooperation, have been inspired by state-run cyber campaigns to improve their level of organization and management. This enhanced orchestration resulted in improved infrastructure, manpower, tools, and capabilities which in turn led to more effective and destructive operations. This began in specific conflict zones but quickly spread globally. In turn, this is expected to inspire hacktivist groups with more diverse agendas.

The boundaries between state cyber-operations and hacktivism are blurred, which allows nation states to act with a degree of anonymity without fear of retaliation. Non-state affiliated hacktivist groups are better organized and more effective than ever before, and this is expected to increase in the future.

The basic layer of cyber protection is recognizing malicious tools and behaviors before they can strike. Security vendors invest substantial resources in the research and mapping of malware types and families, and their attribution to specific threat actors and the associated campaigns, while also identifying TTPs (Techniques, Tactics and Procedures) that inform the correct security cycles and security policy.

To combat sophisticated cybersecurity solutions, threat actors are developing and perfecting their attack techniques, which increasingly rely less on the use of custom malware and shift instead to utilizing non-signature tools. They use built-in operating system capabilities and tools, which are already installed on target systems, and exploit popular IT management tools that are less likely to raise suspicion when detected. Commercial off-the-shelf pentesting and Red Team tools are often used as well. Although this is not a new phenomenon, what was once rare and exclusive to sophisticated actors has now become a widespread technique adopted by threat actors of all types.

There are several reasons why the use of legitimate tools is an attractive option for cybercriminals. First, as these tools are not inherently malicious, they often evade detection and are difficult to distinguish from regular users or IT operations. Second, many of these tools are open-source or available for purchase, so threat actors have easy access to them. In addition, when threat actors share tools, it makes it harder to identify who is responsible for a particular attack.

LotL or LOLBin attacks, which have been around for several years, leverage utilities already available within the targeted system. Attackers use them to download and execute malicious files, conduct lateral movement, and for general command execution. On Windows OS these utilities often involve command shell, Windows Management Instrumentation, and native Windows scripting platforms such as PowerShell, mshta, wscript or cscript. This technique allows attackers to remain under the radar, as legitimate software and native OS binaries are less likely to raise suspicion and are typically whitelisted by default. Attackers often use these utilities for fileless attacks. This leaves fewer traces as no malicious artifacts are written to hard drives, and it makes incident response and remediation work even more complex.

A tight and robust security policy involves constant testing to find vulnerabilities and weaknesses within the network and systems deployed in it. Organizations often rely on the expertise of Red Team professionals to mimic every step of a cyberattack. Red Teams deploy multiple tools to test the resilience of the environment. Many of these tools are free or available for use or purchase in criminal circles and they are often spotted in the wild, in the hands of threat actors.

Cobalt Strike is the most widespread penetration testing tool to be exploited by threat actors, particularly since its source code was leaked in 2020. Brute Ratel is another legitimate offensive framework that uses a licensing process and is currently priced at $2,500. Customers must pass a vetting process before being issued a license to verify that the software will not be used with malicious intent. As cybersecurity solutions are increasingly focused on Cobalt Strike detections, some threat actors quietly switched to Brute Ratel for their 2022 attacks. This includes creating fake US companies to pass the licensing verification system. In an overview report on this tool, techniques associated with APT29 were identified, suggesting it has been adopted by APT-level actors. Researchers also identified the use of the tool by the BlackCat ransomware gang since at least March 2022, which implies that threat actors were able to circumvent the developer’s verification procedure.

As with Cobalt Strike, a cracked version of Brute Ratel was shared in underground cyber-criminal forums in September 2022, leading to predictions that this tool will be widely adopted by threat actors. This is a concerning expansion of the criminal use of Red Team tools, as Brute Ratel was developed by a former Red Teamer with extensive knowledge of EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) technologies and is specifically designed to evade detection by EDR products.

Another emerging offensive framework detected in 2022 is Manjusaka, the Chinese counterpart of Cobalt Strike which is freely available on GitHub. The tool was observed in campaigns targeting the Haixi Mongolian and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture region in China. Additional tools include the Sliver framework, which was seen in multiple campaigns during 2022 and continues to gain popularity at the year’s end.

Earlier this year, Check Point Research uncovered a two year-long campaign targeting financial organizations in French-speaking regions of Africa. Attackers deployed several of these tools, including Metasploit as well as PoshC2, another offensive framework available on GitHub. DWservice is another interesting tool found in this campaign. DWservice is a legitimate remote access service and, while it is subscription-based, it also has a free plan. These are all easy-to-use tools, exploited by actors with varying levels of technical expertise, and we expect to see their use increase at different stages of offensive operations.

Remote Management and Monitoring (RMM) software is used daily for legitimate purposes. Given its destructive potential when used in malicious campaigns, it is crucial to keep a close eye on its use and implement intelligent security policies.

In 2022, multiple ransomware gangs made use of legitimate IT software in successful campaigns. One of the developments was the rise of BazarCall-style social engineering campaigns now employed by multiple ransomware groups. First seen in 2021 when used by the Ryuk/Conti ransomware gang, a BazarCall attack starts with a phishing email that urges the victim to call an actor-controlled call center. The operator instructs the victim to install a potent management tool to be used as malware. This not only allows threat actors to target specific entities based on targeted industry, revenue or other factors. It also leverages social engineering techniques to control the malware delivery process. In multiple campaigns reported in 2022, three separate groups - Silent Ransom, Quantum, and Roy/Zeon – used this method to initiate Zoho Assist sessions, a legitimate remote support tool, which allowed them to gain initial access to corporate networks.

The Conti ransomware group and their affiliates often relied on legitimate remote management solutions such as Splashtop, AnyDesk or ScreenConnect, as well as one-month trial-versions of the Atera agent to regain and establish persistence in cases where Cobalt Strike was previously detected. This is now used repeatedly by their successors. In a CP<R> publication earlier this year, researchers found that Atera remote management tool was used also to deploy the Zloader banker.

In a case investigated by the Check Point Incident Response Team (CPIRT) of a Hello ransomware incident, attackers used Desktop Central, a unified endpoint management solution, together with Atera and Wazuh. Desktop Central was installed prior to the investigated breach, which indicates that it was either utilized legitimately by the IT department - although they did not recognize it as a tool in their use - or was part of a previous breach.

Wazuh is another legitimate software often used by IT personnel. It is not a remote access tool, but rather a security platform used for network asset discovery and vulnerability management. This allows attackers to disguise their activity as legitimate scans for network assets and vulnerabilities.

Other security tools adopted by threat actors include Impacket and BloodHound. BloodHound is a powerful tool for security assessments of Active Directory (AD) environments used in the analysis of AD rights and relations, which can easily be abused by attackers. Impacket is designed for IT administration and penetration testing of network protocols and services. Both tools were exploited by APT groups in high-profile campaigns, such as the WhisperGate destructive operation against Ukrainian organizations, Sandworm attacks against Ukrainian energy facilities together with Industroyer2 malware, and in a Russian state-sponsored campaign targeting defense contractor networks in the US.

Before deploying the Somnia wiper, the FRwL (From Russia with Love) hacktivist group used a toolset consisting of AnyDesk, Ngrok reverse proxy, Netscan network reconnaissance tool, and open-source Rclone for data exfiltration – tools that were previously used in financially-motivated campaigns.

Instead of developing their own malware, threat actors are now using legitimate tools developed and made available by tech companies. This trend sets new challenges for detection, protection, attribution and further mapping of the cyber arena. To meet these challenges, defense systems must employ holistic protection approaches. This emphasizes the operational need for Extended Detection and Response systems (XDR), which provide context-based anomalies-detection and are precisely designed to track down the malicious use of otherwise legitimate tools.

Seeking to maximize the pressure on their victims, ransomware actors employ multiple-extortion tactics. Data on the victims’ systems is encrypted, with decryption keys released only after the ransom payment. Unless they pay, companies know their data could be openly published, sold or even used to extort their employees and customers directly.

Some ransomware affiliates, which have now become more dominant in the ransomware crime scene, and better skilled at identifying sensitive information in victims’ networks, even skip the encryption phase altogether and rely solely on data publication threats to generate ransom payments. This may have serious implications for defense mechanisms, attribution, and future analysis of the ransomware ecosystem.

In the early days, ransomware attacks were conducted by single entities who developed and distributed massive numbers of automated payloads to randomly selected victims, collecting small sums from each “successful” attack. Fast forward to 2022 and these attacks have evolved to become mostly human-operated processes, carried out by multiple entities over several weeks. The attackers carefully select their victims according to a desired profile, and implement a series of pressure measures to extort significant sums of money. Threats of exposing sensitive data have proven to be very effective. This is because the victims fear the consequences of large fines, lawsuits on behalf of employees and customers, and the resulting negative effect on stock prices and reputation.

Ransomware attack-management has also evolved with an increase in threat actors that operate a Ransomware-as-a-Service model (RaaS) through affiliates. Affiliates, who may participate in multiple RaaS programs simultaneously and choose between various encryption tools have become the ”producers”, initiating attacks and paying part of the revenue back to the RaaS operator. Affiliates further outsource operations by purchasing stolen credentials or network access from access-brokers. The fragmented nature of this operation complicates the attribution of attacks and the tracking of criminal entities. Tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) used to gain initial access to a system are no longer necessarily connected to the affiliate or to the RaaS payload later deployed.

Current Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) actors are competing for the attention of affiliates, and typically charge 10% - 20% of the ransom payment as a fee for their services. The speed of the encryption module is one of the main “selling points”, allowing the attacker to reduce the encryption time and probability of detection. RaaS actors’ attempts to shorten encryption time include allowing affiliates to choose from various encryption modes or even offering partial file encryption (“intermittent encryption”).

Some groups now skip the encryption phase altogether, relying on threats of data exposure alone to extort money. In September 2021, a group named Karakurt Team started to employ extortion without encryption. Attacking mostly North American and European victims, Karakurt operators typically contact their victims, provide screenshots and copies of the stolen data, and threaten to auction the information or release it unless their demands are met. They often contact the victims’ employees, business partners and clients to ramp up the pressure. This new behavior, involving direct contact with the victims’ clients, was first observed in 2020, and is referred to as Triple Extortion. Many different types of information are considered sensitive, from corporate financial and proprietary data to personal data relating to physical or mental health, financial data or any other personal identifiable information (PII), which makes the threat of data exposure even more potent.

Negotiation with the victims is often conducted over relatively secure mediums, using proprietary access codes. This is typically done to prevent uncontrolled publication which would result in reduced potential leverage. At least in theory, victims who pay can emerge from an attack relatively unscathed, without their details posted on Karakurt’s shame-site, and thereby stopping their customers or the authorities from finding out they have been attacked.

An example of the effectiveness of the threat of personal data exposure was demonstrated in a recent attack on Medibank, an Australian health insurer, in October 2022. When the company refused to pay ransom demands of $10M, the attackers (possibly connected to the REvil group) dumped massive amounts of personal information relating to pregnancy termination, drug and alcohol abuse, mental health issues and other confidential and highly sensitive medical data relating to millions of Australian and international customers.

The Lapsus$ group also received a lot of public attention following a series of data breaches of large tech companies, including Microsoft, Nvidia and Samsung. Since its first recorded attack in December 2021 on the Brazilian health ministry, in which they stole and threatened to publish medical information regarding COVID-19 vaccinations, the group has focused on data exfiltration rather than encryption. Headed by young criminals of British and Brazilian nationality, Lapusus$ uses various methods to gain initial access to their victims, including payments to employees, purchasing credentials and social engineering. The group focuses on locating and exfiltrating the proprietary source code of their victims’ products. The ensuing threat of publication is estimated to have generated $14M in revenue after only a few months of activity.

Some RaaS actors even recommend their affiliates to avoid encrypting critical areas such as data belonging to healthcare patients. They permit attacking and exfiltrating data from hospitals but not encrypting them, suggesting some twisted version of a moral code among hackers. Hive RaaS, which focuses on healthcare, sometimes makes an effort to not disable the systems. Publishing stolen data has proven effective and threat actors have developed elaborate extortion mechanisms. BlackCat and Lockbit ransomware groups added searchable data mechanisms, allowing employees, customers and other potential victims to search repositories of stolen data. Also, valuable stolen data is often monetized by selling it on Darknet markets.

Other threat actors have turned to destroying data instead of encrypting it. The Onyx ransomware group, active since April 2022, destroys files larger than 2MB instead of encrypting them. Others have followed suit. A new sample of the ExMatter exfiltration tool now includes dedicated wiping functionality. Although it was initially detected as part of the BlackMatter RaaS in late 2021, ExMatter development is attributed to an affiliate and not the RaaS entity. This marks the possible independence of ransomware affiliates from their RaaS partners.

Choosing to base their extortion solely on data publication is understandably attractive to attackers. It offers the option of quick deployment, without a prolonged and messy encryption process, thereby reducing the possibility of detection. Victim management becomes simpler. There is no need to supply individual decryption keys to different victims and operate a logistically complicated “customer support” mechanism. Above all, it frees affiliates from their dependence on large RaaS actors who demand their share of the income.

As this data extortion model becomes prevalent, possible ramifications include increased fragmentation of the ransomware ecosystem. Attribution of ransomware operations and tracking threat actors may become even harder and existing protection mechanisms which are based on detecting encryption activity could prove less effective. In its place, cyber security providers will need to focus more on data wiping and exfiltration detection.

In our 2022 mid-year report we reviewed some major events in the mobile threat landscape, including the vast increase in the number of malicious applications infiltrating Google and Apple stores. Often disguised as innocent applications like QR readers, external Bluetooth apps, flashlights or games, they are designed to attract as little attention as possible. In our latest analysis, we focus on attempts to hide mobile malware in “unofficial” versions of well-known applications. Mostly, these are malicious modified versions (aka Mods), typically distributed through third-party app stores and downloaded by users who prefer an unofficial version for a variety of reasons. This is not a completely unheard of threat, but 2022 has seen multiple attacks using apps that are well known, trusted, and widely used.

Mod APKs (Android Package Kits; applications for Android devices) are reworked copies of well-known applications, designed to provide users with extended functionalities or access that are not available in the original version. In the past few years, we have seen modified versions of a variety of applications, from instant messaging and social media apps, to live streaming, VPN services and more. The apps are usually distributed through unofficial channels to users looking for free versions of known apps, or for additional features that do not exist in the original versions. In some cases, users are targeted and offered direct links to the modified APKs. In others, users seek them out voluntarily due to limited access to official applications. For example, FMWhatsApp allows users to redesign their WhatsApp interface and edit the “last seen” and “blue tick” functionalities. These Mods are not scrutinized as carefully as the official version, which makes them a natural exploitation target for threat actors. Often the infection is achieved through advertisement SDKs, used by the Mods’ developers. This was the case with HMWhatsApp infection with the Triada Trojan in August 2021, and APKPure later that year.

When made aware of these threats, WhatsApp issued an alert in July 2022, warning users not to use modified versions of the app, and described its joint efforts with Google to eradicate previous malicious versions. Despite this warning, another modified build of WhatsApp was reported in October 2022. Once again, the YoWhatsApp Mod was found to contain the Triada malware. When it is implemented in a fully functioning version of the popular messenger app, the malware is granted extensive permissions, including access to SMS messages, similar to the permissions the official WhatsApp app receives. This can allow threat actors to bypass Multi Factor Authentication mechanisms and take over a wide range of applications and accounts, from email to banking and corporate accounts, as well as the WhatsApp account itself. The latest campaign deploying Triada malware through modified applications, which was reported by Check Point Research, weaponized copies of the Telegram messaging app to steal personal information from multiple users.

In most cases, Mods are not distributed through official app stores. However, sometimes unsuspecting users can obtain them through official channels. In October, WhatsApp’s parent company Meta, filed a lawsuit against three companies based in China and Taiwan for developing unofficial versions of the application, and selling them on their websites and in the Google Play Store. Once installed, the modified application was used to hijack accounts and steal sensitive information from more than one million Android users.

Mods have also been used by nation-state actors. In August, researchers exposed the Dracarys Android spyware deployed in a modified version of the Signal messaging application. Despite reports of attacks against its users, Signal is considered a secured messenger, but its modified version provided attackers with extensive spying capabilities along with its regular functions. The operation was attributed to Bitter APT, a group known to operate in South Asia, which is reportedly also producing similar Mods for Facebook, Telegram, YouTube and WhatsApp. The attack was deployed using phishing sites that mimicked the genuine Signal site, and most likely targeted users through phishing emails and social media. Meta also accused Transparent Tribe (APT-36), a Pakistan affiliated state-sponsored threat actor, of creating and using fake versions of WhatsApp, WeChat and YouTube, and identified more than 10,000 potentially affected users.

Malicious modified versions of two mobile VPN applications, SoftVPN and OpenVPN, were used to spy on users by the mercenary Bahamut APT group, which offers hacking services to a wide range of clients.

Populations of totalitarian regimes often have limited access to applications in the official app stores and must seek other alternatives. This makes them more susceptible to attacks by financially or politically motivated actors. This was the case in 2018 and 2019 when the Iranian government blocked secure instant messaging (IM) apps, resulting in an increase in cloned unofficial versions of Telegram, Instagram and other IM applications. Many of the unofficial applications were later revealed as part of a government program to spy on and control opposition and minority groups.

Mobile devices are targeted by hostile entities for a variety of reasons and motivations. Attackers often target the most popular, well- known and widely used applications which users would consider safe. Exploits can come in either the form of modified or fake applications, or through the exploitation of vulnerabilities in the original versions. We should take this as a reminder of the need to stay vigilant, especially when using the most popular and widely used applications.

Over the past few years, Check Point Research (CP<R>) has been tracking the increasing adoption of cloud infrastructure in corporate environments, as well as the evolution of the cloud threat landscape. Currently, around 98% of organizations use cloud-based services, and 76% of them have multi-cloud environments that incorporate services from two or more cloud providers.

When comparing the past two years, we have seen a significant increase in the number of attacks on cloud-based networks per organization, which shot up by 48% in 2022 compared with 2021. Although the overall number of attacks on cloud-based networks is 17% lower than non-cloud networks, a closer examination of the types of attacks shows that newly disclosed vulnerabilities (2020-2022) are exploited more frequently on cloud-based than on-premise environments. This might indicate a shift that some threat actors now prefer to scan the IP range of cloud providers. This might enable to gain easier access to sensitive information or critical services.

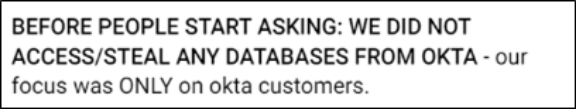

In addition to vulnerability exploitation attempts, cloud environments have become both a source and target of security incidents and breaches that involve improper access management, sometimes combined with the use of compromised credentials. In March 2022, the ransomware gang Lapsus$ announced in a statement on its Telegram channel that it had gained access to Okta, an identity management platform. Lapsus$ has a history of publishing sensitive information, often source code, stolen from high-profile tech companies such as Microsoft, NVIDIA, and Samsung. However, this time, the actors claimed their target was not Okta itself, but rather its customers.

Following the breach, Okta released an official statement revealing that approximately 2.5% of their customers were affected by the Lapsus$ breach—around 375 companies, according to independent estimates. Okta, is used by thousands of companies to manage and secure user authentication processes, as well as by developers to build identity controls. This effectively means that hundreds of thousands of users worldwide could potentially be compromised by the company responsible for their security.

On its Telegram channel, Lapsus$ claimed that Okta was storing AWS keys in Slack and that Okta’s third-party support engineers had access to all the company’s 8,600 Slack channels. It is possible that Lapsus$ gained initial access to Okta via Slack using stolen cookies and/or social engineering. CP<R> suggested that Lapsus access to Okta clients could explain the cybercrime gang’s modus operandi and impressive record of successes, all thanks to excessive permissions granted to a third-party within the corporate cloud environment. Identity and Access Management (IAM) role abuse attacks were thoroughly discussed by CP<R> in 2021, and while this is still an ongoing issue, there are other risks of which businesses need to be aware.

On September 16, 2022, Uber stated that they were responding to a security incident which they later attributed to a hacker connected to the very same Lapsus$ group. The company explained that the attacker used stolen credentials of an Uber contractor in a Multi Factor Authentication fatigue attack, where the contractor was flooded with two-factor authentication (2FA) login requests until one of them was accepted. These credentials were then used for lateral movement and privilege escalation that resulted in the intruder gaining administrator access to Uber's AWS cloud account and its resources.

Towards the end of the year, Uber suffered another high-profile data leak that exposed sensitive employee and company data. This time, attackers breached the company by compromising an AWS cloud server used by Tequivity, which provides Uber with asset management and tracking services. It is not clear if the unauthorized access was due to misconfiguration or stolen credentials, but it’s evident that we need to adapt our methods of assessing third-party risk to the world of cloud infrastructure.

From basic rules like not storing cloud access keys publicly or not ignoring 2FA bypass attempts, to more complicated but essential ones such as prevention of cloud misconfigurations and using proper IAM, the events of 2022 show that any violations of these rules puts cloud environments at risk.